This article was inspired by

, where she sent us this prompt:I’d love to know whether there is a fairy tale which is nagging at you right now, or one that you’ve loved and that has stayed with you for a long time, and which reflects or illuminates a major challenge you’ve previously faced or are facing now in your life. What’s the fairy tale; what situation did it shed light on, and at what stage of your life? In other words, has a fairy tale ever informed or illuminated a specific stage of your journey? And is there a character or image from the story which still haunts you or has lodged itself in your mind and which still has something to say to you today?

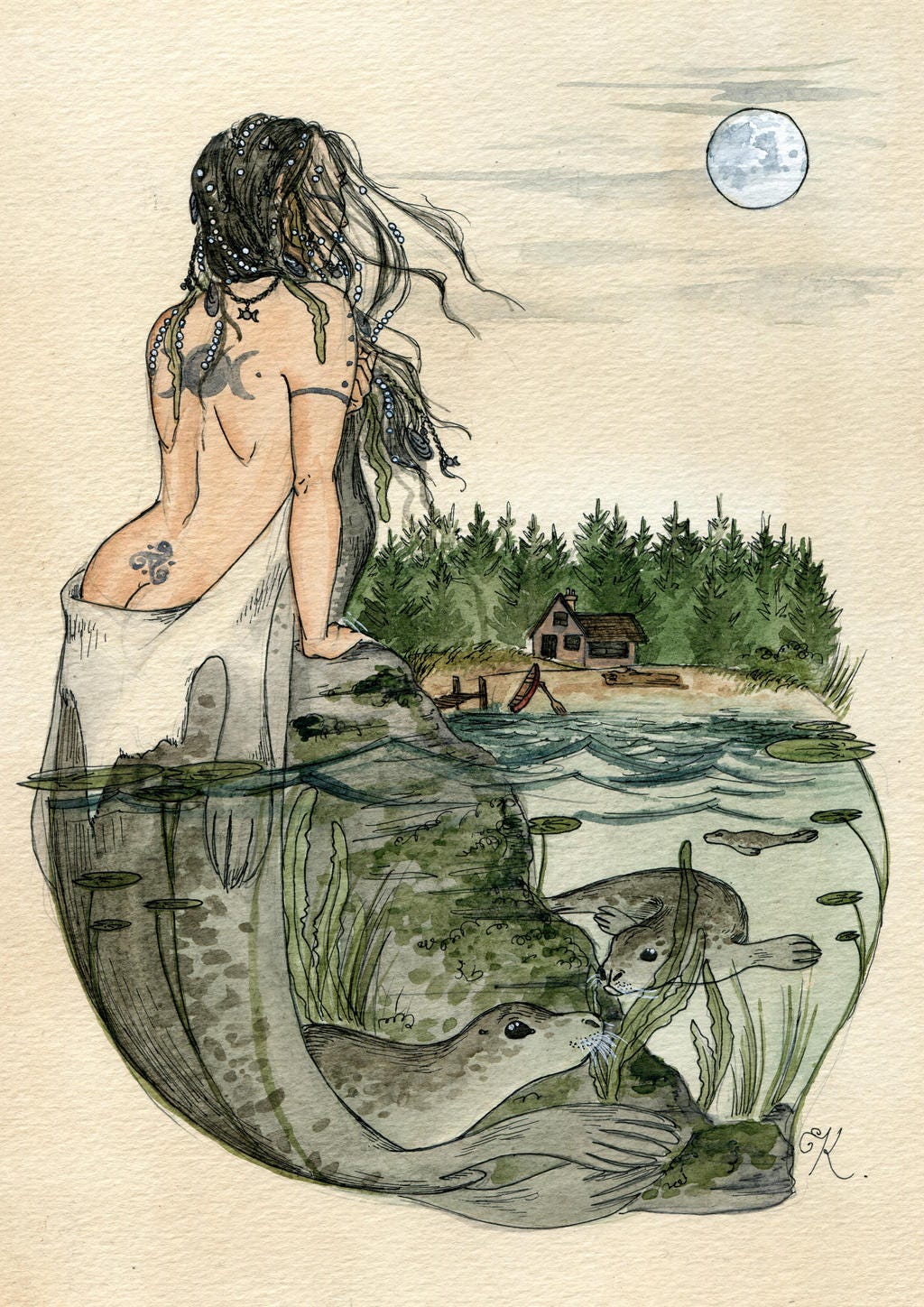

It’s funny, because the this archetype feels very alive to me, now. In part because I am starting to work intentionally on my next poetry book, which is very sea-related, and also because the themes of freedom and change are so prevalent in my life now, and also because we are in the last days of Pisces Season.

The folk tale I refer to is that of the seal-woman losing her pelt.

I was first introduced to the story in Dr. Clarissa Pinkola Estés book, Women Who Run With the Wolves, and something about it stuck with me. Not just in the manner of which she speaks of it—that of losing one's pelt / soul, but also in the loss of freedom versus duty.

Before I go further, here is the tale as told by Dr. Estés:

Sealskin, Soulskin

DURING A TIME that once was, is now gone forever, and will come back again soon, there is day after day of white sky, white snow... and all the tiny specks in the distance are people or dogs or bear.

Here, nothing thrives for the asking. The winds blow hard so the people have come to wear their parkas and mamleks, boots, sideways on purpose now. Here, words freeze in the open air, and whole sentences must be broken from the speaker's lips and thawed at the fire so people can see what has been said. Here, the people live in the white and abundant hair of old Annuluk, the old grandmother, the old sorceress who is Earth herself. And it was in this land that there lived a man so lonely that over the years, tears had carved great chasms into his cheeks.

He tried to smile and be happy. He hunted. He trapped and he slept well. But he wished for human company. Sometimes out in the shallows in his kayak when a seal came near he remembered the old stories about how seals were once human, and the only reminder of that time was their eyes, which were capable of portraying those looks, those wise and wild and loving looks. And sometimes then he felt such a pang of loneliness that tears coursed down the well-used cracks in his face.

One night he hunted past dark but found nothing. As the moon rose in the sky and the ice floes glistened, he came to a great spotted rock in the sea, and it appeared to his keen eye that upon that old rock there was movement of the most graceful kind.

He paddled slow and deep to be closer, and there atop the mighty rock danced a small group of women, naked as the first day they lay upon their mothers' bellies. Well, he was a lonely man, with no human friends but in memory—and he stayed and watched. The women were like beings made of moon milk, and their skin shimmered with little silver dots like those on the salmon in springtime, and the women's feet and hands were long and graceful.

So beautiful were they that the man sat stunned in his boat, the water lapping, taking him closer and closer to the rock. He could hear the magnificent women laughing... at least they seemed to laugh, or was it the water laughing at the edge of the rock? The man was confused, for he was so dazzled. But somehow the loneliness that had weighed on his chest like wet hide was lifted away, and almost without thinking, as though he was meant, he jumped up onto the rock and stole one of the sealskins laying there. He hid behind an outcropping and he pushed the sealskin into his quinguq, parka.

Soon, one of the women called in a voice that was the most beautiful he'd ever heard... like the whales calling at dawn... or no, maybe it was more like the newborn wolves tumbling down in the spring... or but, well no, it was something better than that, but it did not matter because… what were the women doing now?

Why, they were putting on their sealskins, and one by one the seal women were slipping into the sea, yelping and crying happily. Except for one. The tallest of them searched high and searched low for her sealskin, but it was nowhere to be found. The man felt emboldened—by what, he did not know. He stepped from the rock, appealing to her, "Woman... be... my... wife. I am... a lonely... man."

"Oh, I cannot be wife," she said, "for I am of the other, the ones who live temeqvanek, beneath."

"Be... my... wife," insisted the man. "In seven summers, I will return your sealskin to you, and you may stay or you may go as you wish."

The young seal woman looked long into his face with eyes that but for her true origins seemed human. Reluctantly she said, "I will go with you. After seven summers, it shall be decided."

So in time they had a child, whom they named Ooruk. And the child was lithe and fat. In winter the mother told Ooruk tales of the creatures that lived beneath the sea while the father whittled a bear or a wolf in whitestone with his long knife. When his mother carried the child Ooruk to bed, she pointed out through the smoke hole to the clouds and all their shapes. Except instead of recounting the shapes of raven and bear and wolf, she recounted the stories of walrus, whale, seal, and salmon... for those were the creatures she knew.

But as time went on, her flesh began to dry out. First it flaked, then it cracked. The skin of her eyelids began to peel. The hairs of her head began to drop to the ground. She became naluaq, palest white. Her plumpness began to wither. She tried to conceal her limp. Each day her eyes, without her willing it so, became more dull. She began to put out her hand in order to find her way, for her sight was darkening.

And so it went until one night when the child Ooruk was awakened by shouting and sat upright in his sleeping skins. He heard a roar like a bear that was his father berating his mother. He heard a crying like silver rung on stone that was his mother.

"You hid my sealskin seven long years ago, and now the eighth winter comes. I want what I am made of returned to me," cried the seal woman.

"And you, woman, would leave me if I gave it to you," boomed the husband.

"I do not know what I would do. I only know I must have what I belong to."

"And you would leave me wifeless, and the boy motherless. You are bad."

And with that her husband tore the hide flap of the door aside and disappeared into the night.

The boy loved his mother much. He feared losing her and so cried himself to sleep... only to be awakened by the wind. A strange wind... it seemed to call to him, "Oooruk, Oooruuuuk."

And out of bed he climbed, so hastily that he put his parka on upside down and pulled his mukluks only halfway up. Hearing his name called over and over, he dashed out into the starry, starry night.

"Oooooooruuuuk."

The child ran out to the cliff overlooking the water, and there, far out in the windy sea, was a huge shaggy silver seal... its head was enormous, its whiskers drooped to its chest, its eyes were deep yellow.

"Oooooooruuuuk."

The boy scrambled down the cliff and stumbled at the bottom over a stone—no, a bundle—that had rolled out of a cleft in the rock. The boy's hair lashed at his face like a thousand reins of ice. "Oooooooruuuuk."

The boy scratched open the bundle and shook it out—it was his mother's sealskin. Oh, and he could smell her all through it. And as he hugged the sealskin to his face and inhaled her scent, her soul slammed through him like a sudden summer wind.

"Ohhh," he cried with pain and joy, and lifted the skin again to his face and again her soul passed through his. "Ohhh," he cried again, for he was being filled with the unending love of his mother.

And the old silver seal way out ... sank slowly beneath the water.

The boy climbed the cliff and ran toward home with the seal-skin flying behind him, and into the house he fell. His mother swept him and the skin up and closed her eyes in gratitude for the safety of both.

She pulled on her sealskin. "Oh, mother, no!" cried the child. She scooped up the child, tucked him under her arm, and half ran and half stumbled toward the roaring sea.

"Oh, mother! No! Don't leave me!" Ooruk cried.

And at once you could tell she wanted to stay with her child, she wanted to, but something called her, something older than she, older than he, older than time.

"Oh, mother, no, no, no," cried the child. She turned to him with a look of dreadful love in her eyes. She took the boy's face in her hands, and breathed her sweet breath into his lungs, once, twice, three times. Then, with him under her arm like a precious bundle, she dove into the sea, down, and down, and down, and still deeper down, and the seal woman and her child breathed easily under water.

And they swam deep and strong till they entered the underwater cove of seals where all manner of creatures were dining and singing, dancing and speaking, and the great silver seal that had called to Ooruk from the night sea embraced the child and called him grandson.

"How fare you up there, daughter?" asked the great silver seal.

The seal woman looked away and said, "I hurt a human...a man who gave his all to have me. But I cannot return to him, for I shall be a prisoner if I do."

"And the boy?" asked the old seal. "My grandchild?" He said it so proudly his voice shook.

"He must go back, father. He cannot stay. His time is not yet to be here with us." And she wept. And together they wept.

And so some days and nights passed, seven to be exact, during which time the luster came back to the seal woman's hair and eyes. She turned a beautiful dark color, her sight was restored, her body regained its plumpness, and she swam uncrippled. Yet it came time to return the boy to land. On that night, the old grandfather seal and the boy's beautiful mother swam with the child between them. Back they went, back up and up and up to the top-side world. There they gently placed Ooruk on the stony shore in the moonlight.

His mother assured him, "I am always with you. Only touch what I have touched, my firesticks, my ulu, knife, my stone carvings of otters and seal, and I will breathe into your lungs a wind for the singing of your songs."

The old silver seal and his daughter kissed the child many times. At last, they tore themselves away and swam out to sea, and with one last look at the boy, they disappeared beneath the waters. And Ooruk, because it was not his time, stayed.

As time went on, he grew to be a mighty drummer and singer and a maker of stories, and it was said this all came to be because as a child he had survived being carried out to sea by the great seal spirits. Now, in the gray mists of morning, sometimes he can still be seen, with his kayak tethered, kneeling upon a certain rock in the sea, seeming to speak to a certain female seal who often comes near the shore. Though many have tried to hunt her, time after time they have failed. She is known as Tanqigcaq, the bright one, the holy one, and it is said that though she be a seal, her eyes are capable of portraying those human looks, those wise and wild and loving looks.

I encountered the tale again in the Irish folk song An Mhaighdean Mhara via Madelyn Monaghan and fell in love, perhaps because it is also known as the Mermaid—a character I've been in love with since a little girl. (All my Ariel girlies, stand up! But even beyond the Disney glitter-glossed version, a mermaid was what I dreamed to be.)

At the core of these stories, and what captures my imagination and psyche, is the idea of freedom versus being held static by obligations. Though not married nor having any children of my own, at a very young age I was forced to grow up quickly to care for my younger sisters (a habit I am attempting to break free of) but also attached to me is the idea that I must care of my parents / elders.

Though not opposed to the idea and action of filial piety, what I struggle against is the idea that I alone am expected, or obligated, to be such for my mother and grandmother. Let it be known—these obligations are not directly placed upon me (no-one has explicitly said I have to), but rather, in certain ways, the accumulation of expectations and actions have been emphasised to me.

To get a bit personal—I am 31 years old, and moved to be on my own last September. It is not uncommon for children to live with their parents til they marry in my country and actually, it is still quite common to have 3 generations in one home—but as I lived on my own when studying abroad, having moved back to live under my mothers' roof was stifling. However, when I mentioned my decision to my grandmother, her one and only objection was that I was "leaving my mother all alone." My mother is a very capable and active woman, and beyond that, my youngest sister still lives with her (thereby she will not have, under any circumstance, been "left home all alone").

This all coincides with my own desire to explore who I am, what I am called to do, as well as discover who I am when left on my own. What will flourish? What will pass on? What will stay the same, and what will change? (To quote Moana—the sea, it calls me). Very, in my mind, seal-woman, mermaid-esque questions (“but something called her, something older than she, older than he, older than time.”) But never to forget where I came from. Never to fully leave behind. Always with one foot in the world of my own creation, one from whence I came.

The seal-woman / mermaid archetype is a woman's separation from her family, from her obligations, outside of marriage. A stage of life more and more women, in my experience, are coming upon as we embrace independence, as we move into working life. No longer are women expected to move from their parents' home to their husbands'; there is now that in-between, liminal space between where they explore who they are when having "no chick, no child".

the lonely beauty

in a whale’s song

echoes

in my tendons,

in my marrow,

and I yearn to be

the mermaid

I was

before

I grew up.

—Shattered Galaxies, pg. 59

A recent struggle of mine has been this balancing of exploring my freedom versus the deep-seated and ingrained duty I feel towards my mother (and grandmother). Where is the line between the generations drawn? Where am I giving too much of myself, out of habit, out of always being the good daughter who is there with a listening ear and helping hands? And how far can I go without feeling I have to look back—before I feel I even want to look back?

In a sense, this freedom scares me. Because a part of me wonders if I go too far beyond the surf…I won’t come back. What then? Like the seal-woman, would I leave behind all I’ve come to love? Without a set “home” to return to, will I wander on forever? (“I only know I must have what I belong to.”)

I believe every woman has these questions within them, quietly pushing at the boundaries of their being: to go further, to see how far we can go. Who will we be without society’s expectations of being someone’s daughter? Someone’s sister? Someone’s wife? Someone’s mother? Someone’s home?

I believe that we, as a people, place a lot on our daughters’ shoulders. Not just modern society, but generationally; while men have been celebrated for exploring, for pushing the frontier, for their “walkabouts”, women who do the same are seen as different. Not normal. (“Oh, you’re not like other girls.”)

Oh, but what if we embrace our inner mermaid, our inner selkie—to be lost in the deeps, to have the ocean unfurl before us, with nothing pulling us back, and only the stars to guide our way?

The man in the tale traps the selkie by hiding her pelt, securing her to his side through trickery and removing from her an integral part of her being. According to Dr. Estés, it is symbolic of every woman’s soul—and regaining the pelt represents a call back to soul, to what was and what always will be, the core essence of us. (“I want what I am made of returned to me.”)

The tale of the selkie is the tale of return. And we don’t know that we will return, only that we must go in search of it, however many times, we must heed the call.

I see in the women around me, and in the world, our slow reclamation of our pelts. Our wildness. Our freedom. Our soul-calls that we answer. Away from our homes, the expectations, the duty, the things we were told we have to be, or have to want, or have to have.

So, let it all go. Cast off your human-self and embrace the inner selkie… and dive.

See what arises on the horizon for you.

With deep reverence and a calling to other selkies,

ᛝBritt

Post-Scripts 🌊

🌊 Another aspect of the mermaid archetype is the realm of imagination, of fantasy. Of dwelling within the inner reaches of our dreams—the ones at night, and the ones we conjure during the day. But at what point do we become “delulu”? (And is delulu the solulu?) I love to encourage those around me to dream—to look past the horizon to a world of their own creation. But I also ask them how to action it, day by day. What is the point of dreaming of a better world if we do not then try to create it?

🌊 This section, which I have labelled Breathing Life, is centred on folk-tales and how I see it reflected in my life—and the world around me. Because I believe it is important to keep breathing life into these stories, into the lore, to pass it on to others…Because stories are medicine.

To read the previous one on our Maman D’Leau and how she guided me in writing with Feroza on our song, Bring Me Back (To the Riverside), check it out here:

River me.

I love the phrase “river me”. There is something so compelling, so evocative to it… it brings to mind lazy days lying on the riverbed, allowing the river’s water to flow over and around my body. It brings to mind the playfulness of a waterfall, the giggles barely heard over its rush. It brings to mind quiet contemplation and companionable silence with a…

🌊 Here is the post from Dr. Sharon Blackie which sparked this article. I encourage you, if you enjoyed this, to check her out—she goes so much more in depth in these topics than I ever can:

🌊 And, of course, if this story and theme speaks to you and you not yet gotten your hands on a copy of Women Who Run With Wolves… What are you waiting for?

I do not speak from a psychology background or with any other credentials other than a woman who feels deeply and loves folklore and mythology, and cannot help but see it reflected in her daily life—and have a deep desire to share what I learn. As someone still learning, I will always be happy to hear any other recommendations, or even your own opinions, on these subject matters.